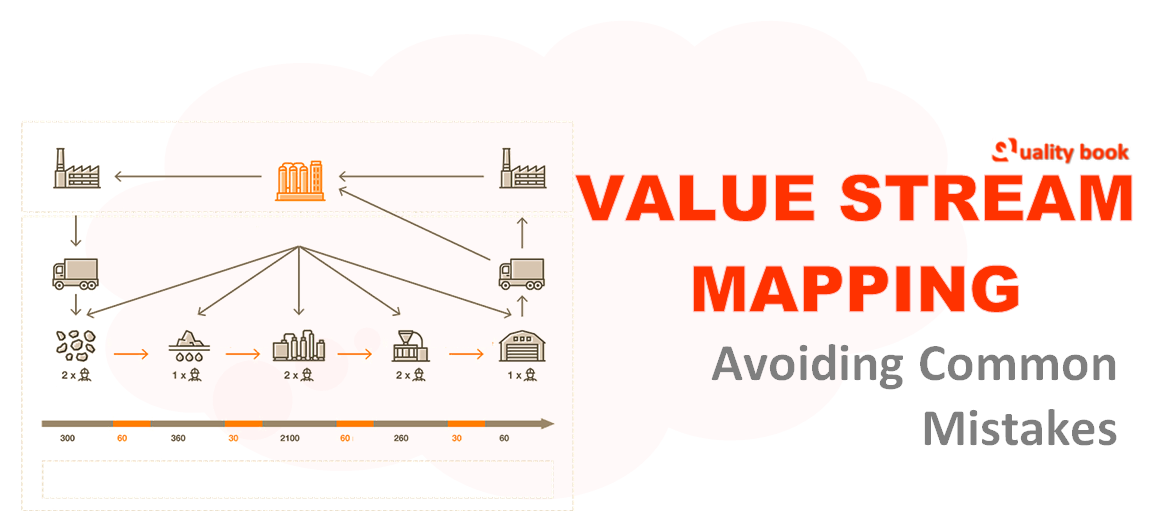

The accurate value stream diagram may help you to avoid complexities, highlight the importance of product family analysis, identify utilization of resources, and separate inventory causes from actual processes.

Confusion about Product families

When reviewing the value stream diagram submit by the supervisor. It is sometimes found that there are many small value flows in and out of the main value stream diagram. Which looks very complex and increases the difficulty of analysis.

This problem occurs mainly because the product family analysis before starting the diagram analysis is not done well. Some product families are very obvious, such as home appliance companies producing different models of TVs, microwave ovens, refrigerators, etc.

You can know it at a glance; Some are not very obvious, such as electronic parts manufacturers, hundreds of products, or even thousands of kinds, product types are similar, product processing processes are complex, less than a dozen, more than dozens, among which there are many branches and convergence places. It is generally believe that, if the process processing process of the research object reaches more than 80%. The same can be judge as the same product family.

During the analysis process, if the shared resources in the process are not well identify. And the flow of appropriate products or people is not well tracking method. The value stream map is often very complex. Does not reflect the true situation of the product family, and even goes further and further down the wrong path.

Example for value stream diagram

For example, existing subject A is process on a lathe and then sent to the warehouse for transportation. This machine is also use for the processing of another product B. Which is also processing by welding, grinding, and assembling three processes, and then put into storage for delivery.

Machine tools are a shared resource here, and product B already belongs to another product family. If this situation is not correctly identify. It is likely that the welding, grinding and assembly will be analyze according to the value stream of product B, and it is correct that we should go directly from the machine to the warehouse.

Before starting the value stream mapping, make sure you already know the relevant product family.

Ignore Shared Resources

In many cases, there are shared resources in the process. Shared resources refer to resources that support/serve more than one family of products, be people, entire assembly lines, or a single machine.

For example, an injection molding company mainly produces mobile phones and MP3s, and a machine in the spraying workshop specializes in spraying all smaller parts, including mobile phones and MP3s All kinds of gadgets.

Another example is the sending and receiving area of the warehouse, where all kinds of goods and raw materials are received or sent. In both examples, the spray machine and the receiving area are shared resources, including the staff here. If you forget this, it is easy to draw the wrong conclusion.

For a simple comparison:

Let’s say that the area serves two heavy workshops.

Each producing an average of 80 products per day, for a total of 160 products a day, or an average of 20 per hour pieces.

That is 10 pieces per workshop.

If a transceiver can do 10 things an hour, two transceivers are obviously need to work in this position. If the workload for only one product family is incorrectly calculation in a value stream diagram, it can lead to the impression that only one person is needed in the role.

Maybe this example is too simple, but when you are faced with hundreds of products and many product families, there may be mistakes that miss or ignore some product families. So be sure to pay attention to whether it is a shared resource.

Remember to identify shared resources correctly. Otherwise it will lead to important calculation errors such as both takt time and cycle time.

Double-count time

When preparing to fill the information box with observations, be sure to think clearly about what the process steps are. What should be put into the data frame, and what should not be. For example, the Changeover time that occurs is known to be put in the data frame, because that’s what the book says.

But there are still people who don’t understand why it’s not listed separately, with a separate record on the lead time. Another example is walking time, assuming that it takes 15 minutes to walk around between two processes, should a separate data frame be drawn on the value stream diagram? Are the two times mentioned earlier considered process processing time? Do you want to put it in the data frame?

The key here is to separate the causes of inventory build-up from the actual product or service processes, not to be much confusing.

As mentioned above, too long changing time and walking distance often cause inventory accumulation in a certain place / post of the process. Which is the cause of various forms of inventory in the enterprise. In fact, it is the place where we implement lean production to eliminate. This is not the real process of a product or service. When we count the inventory, we actually include these factors in the lead time.

When conducting a value stream analysis, analyze what causes inventory backlogs and what are the actual process steps to process a product or service.

Hearsay

This is somewhat similar to point five, which refers to staying in the office without going deep into the field to complete the value stream diagram. The author has counselings many enterprise cadres. Who are generally in middle management positions in enterprises, and found that they are reluctant to go into practice in many cases.

In today’s common use of computers, a lot of data will be stored in computers. When mapping value streams, some people are reluctant to go deep into the front line of the shop floor to observe, preferring to stay in the office and call up data from computers (such as inventory levels).

Another situation is to listen to the field data provided by others (such as asking subordinates to find the data and then report back), but the data itself is not confirmed and has great differences. From a technical point of view, some data can indeed be obtained from files or data stored on computers, and a general flowchart can be pieced together.

For example, how many operations there are in a process, how many operators, how much inventory is in the warehouse, how is the layout of the workshop, and how much distance is traveled.

But being technically correct doesn’t mean that the situation is the same in practice, and the actual situation can vary widely. If someone doing a value stream mapping doesn’t go deep into the shop floor, they lose a lot of where they observe waste.

Example

For a simple example, an operator in a packaging position needs to remove electronic products from the iron plate, put them in a carton neatly arranged, and then pack them in plastic film and put them on the shelves for yards, and the standard working time is 3 minutes per pack. But in fact, when you go to observe, you find that 10 minutes have passed and are not finished.

Looking closely, it was found that because the iron plate was recycled. The packer also had to send the vacated iron plate back to the previous two processes, every 5 minutes, walking 15 meters. In addition, because it is close to the internal telephone in the factory. The phone often rings, and he is also responsible for answering the phone and conveying it. All this work would not have been detected without going to the site to observe. But in fact it was this packer who was doing it.

So, if you don’t go deep into the field, you can’t find out why the factory takes so long to produce. In the daily operation of enterprises, there are many actual operations and processes that are not recorded, are not officially listed as standard procedures, but in fact exist.

Genuine situations

Refers to value stream mapping without actually producing a product or providing a service. Sometimes certain products are not produced often or happen not to be produced in the recent period. Or the production cycle is too long, but the value stream needs to be analyze. (Sometimes from the customer, sometimes from management).

As a result, value stream mapping is done without “seeing” existing operational data and engineering standards (e.g., data provided by production or IE). What’s more, the so-called “benefits” of the project are calculated from this!

They forget some of the basic principles of lean manufacturing.

First, without actually looking at the various inventories in the process. They actually get a process map, not a value stream diagram.

Second, without observing how the time measurements in the value stream diagram came about. They couldn’t identify the waste and opportunities for improvement.

In addition, the value flow of closed-door vehicles often ignores some details in actual operation, and the difference between it. The actual operation will cause front-line operators to be very confuse and lose their due guidance value.

For value stream diagram, the author recommends doing it at least once a month to observe. The actual situation in different situations and make comparisons.

Mis-selected tracking object

It is clear that when doing value stream mapping, the object of choice to track is a product or service. Suppose you are a product flowing through the process and observe what changes in shape, function, and packaging.

In the general manufacturing process: Raw materials in physical form. Semi-finished products and finished products are still relatively clear and are not prone to errors.

But in the service industry or administrative office environment, sometimes mistakes are made. Because in a service environment, people in certain areas will leave or transfer jobs. The “product” has actually change or shift, but we will still keep track of the original object.

To take the example of a dental office, the “product” we track should be the patient. Suppose the patient enters the consultation room from the beginning, registers, sits down, and waits. When it’s their turn to call. The patient is led by a nurse into the doctor’s office, talks, treats, and then leaves the clinic. Does our tracking end here? No way.

In fact, when a patient leaves.

The clinic nurse may have to clean up the instruments.

Sort out the medical records.

Enter the results into the computer archive, and

Then call the next patient.

The process does not stop immediately after the “product” leaves.

But changes the form of existence to the instruments and documents that need to be process. In the above case, we should stop following the patient and start observing what the nurse is doing.